Sleepr

UX Design

How do I stop looking at my phone, and fall asleep?

Sleepr helps young adults control their sleep procrastination by customizing a screen time plan for the apps they enjoy using while in bed.

⭐️ Featured in DesignRush’s Best Design Awards of 2023 - 2024

Project Overview

📁 Project type: BrainStation Capstone Project

📅 Timeline: 10 weeks, Jun-Aug 2021

👔 Roles: UX Researcher, UX/UI Designer, Marketing Strategist

🛠️ Tools:

My Approach

I followed the double diamond design framework during this project, with an additional three stages that focused on the go-to market strategy.

Research & Discovery

Problem Space

Sleep and mental health

During my two years as an resident assistant in university, I had first hand experience with the mental health crisis in upper education. My first-year student communities were disconnected from a sense of well-being, and failing to cope with the stressors of university. Along with students from all campuses, they demanded for the university to investigate systemic problems in its network of mental health resources, and propose a solution.

As a staff member I got to interact with students everyday, and began to observe my peers new relationship with sleep. There was a belief that success was dependent on how much sleep we were willing to sacrifice. I learned about the consequences of this idea through my experiences on the job. Mostly by responding to an alarming number of students with suicidal thoughts. This idea about sleep fueled the mental health crisis, leaving us vulnerable to the effects of sleep deprivation at the time and after graduation.

Poor sleep quality is linked to a weakened immune system, and mental health problems like anxiety and depression. The sleep-deprived student/young professional stereotype is a symptom of my generation’s struggles with mental health, and evidence for the need to rekindle our relationship with sleep.

Secondary Research

Sleep deprivation

Firstly, I wanted to understand the scale of sleep deprivation.

I found that insufficient sleep is an overlooked global public-health epidemic. With the 2019 Phillips Global Sleep Survey reporting that 62% of adults worldwide feel they don’t get enough sleep, averaging 6.8 hours on a weeknight compared to the recommended amount of 8 hours. Respondents gave various reasons for this shortfall, including stress and their sleeping environment, but 37% pointed to their hectic work or school schedule.

Young adults, 18 to 25 years old, report sleeping for less than the recommended 8 to 10 hours for their age group. This presents a long-term problem, since it’s been shown that problems in sleep quality at an early age, predict problems in sleep quality at an older age. But the effects of low-quality sleep are more present on a daily basis. With some researchers suggesting that sleep deprivation is comparable to alcohol intoxication. In fact, it’s easy to experience sleep deprivation if we are not conscious of our sleep debt. Which is when a person grows more tired for every day they don’t get enough sleep.

The combination of hectic work schedules and sleep debt cycles becomes more problematic when we introduce the effects of the “attention economy.”

As a young adult, social media is an outlet for me to feel connected with the world and culture. However, that connection comes with a sophisticated attempt to monopolize my attention. With the cost being a chunk of time that often goes beyond my initial willingness to pay. Because of this, I end up falling into patterns of behavior that delay the things I want to do. Especially at night, when I’m the most active on my device.

Technology and sleep

The consensus among researchers is that late night technology use is detrimental to our sleep quality for a variety of reasons. For example, the repeated use of a bright screen over 5 days can delay the body clock by 1.5 hours. Causing us to delay our bedtime and sleep in longer.

Late night technology users also report less satisfactory sleep more often, compared to those that don’t use technology before bed. However, a recent anthropological study showed that the reported sleep of a hunter gatherer community with no access to artificial lights, was similar (and sometimes even worse) than their western city-living counterparts. This shows that the presence of technology alone being the main cause of low sleep quality, is an oversimplification of the problem.

Because our sleep is greatly dictated by genetics, I chose to search for an insight within our behaviors with technology in bed. My rationale was that I could better formulate the problem by investigating activities that directly influence our sleep. This, and my previous research would help me define part of our current relationship with technology, and its effect on our sleep.

A behavior problem

As I chose to focus on our behaviors with technology, I found a new design constraint:

How do I use technology to change my user’s behavior, and how they engage with technology itself?

I needed more information before moving forward. But this time, it had to come from my target audience. So I put together a design challenge, and a plan to gather primary research from a group of young adults.

Design Challenge

“How might we…”

With my secondary research, I developed my first design challenge statement:

Interview Insights

Talking to young adults

To understand how my target user viewed their relationship with technology and sleep, I conducted six 30 minute interviews with young adults ages 18-25. All participants had no previous history of sleep problems, access to digital devices before or in bed, and were currently living in North America.

I prompted participants to self-report their levels of sleep deprivation using the modified BEARS screening medical tool to diagnose sleep problems. Then, I asked them questions about their sleep hygiene, bedtime habits, daily schedule, and the role of technology in their sleep.

In this process I gathered qualitative data. It included the participants attitudes and behaviors towards their current sleep habits, as weel as their use of technology before bed. I analyzed the interview notes for each participant, extracted quotes, and classified them under three categories:

Behaviors

Motivations

Pain points

With this categorization I extracted five themes that provided me with insights into the problem space. After reviewing each theme, I chose two core insights to move forward with in my solution.

Synthesis

Refined Design Challenge

At this stage, I refined my design challenge to reflect the insights I had gathered from my target market.

In this new version, I attempt to reframe the problem space. Firstly, by establishing the use of technology at bedtime as a starting point. And secondly, by stating that my target user wants to fall asleep earlier and improve their sleep quality. Lastly, since most interview participants reported wanting to use their phones at night, it was appropriate to design around it rather than against it.

User Persona & Experience Map

Empathizing

To synthesize my research findings, I developed an user persona profile and user experience map. These tools helped me keep the target user in front of mind, and weigh my design decisions against the research insights.

Meet Lucy

Lucy Chang is 22 years old, and a recent graduate. She currently goes to bed at around midnight with the hopes of falling asleep soon, but ends up using her phone in bed past 1 a.m. in the morning. She finds it entertaining to use her phone in bed, but wants to put a hard stop on it so that she can fall asleep earlier. She wants a quick and easy way to manage her screen time in bed and remember when to put away her phone.

To create my user’s experience map, I explored what a weeknight looks like for Lucy. In the process, I stepped in Lucy’s shoes, broke down her nightly routine, and waged the value for interventions in different areas.

Research expansion

Refining

Through my primary research I narrowed my focus on sleep procrastination and it’s impact on sleep quality. I felt the need for an additional round of secondary research because I lacked information on the nature of sleep procrastination, and the psychology behind it.

Revenge bedtime procrastination

In my research, I found that revenge sleep procrastination is a modern phenomenon that the research community had only recently started to investigate. It’s seen as the decision to sacrifice sleep for leisure time, driven by a desire to “get revenge” at a packed daily schedule with little free time.

We know it’s sleep procrastination because of three things. There’s a delay in sleep time, there’s no valid reason for staying up late, and the person is aware that this may lead to negative consequences. There are two types of sleep procrastination: bedtime procrastination and while-in-bed procrastination. The former is delaying the act of getting in bed, and the latter is pushing back falling asleep once in bed. Overall, the increase in sleep procrastination is correlated with the increase in the use of mobile devices in bed.

I decided to tackle while-in-bed procrastination with my intervention because it fitted with the insights I gained through primary research. Also, this type of procrastination aligned well with the narrative of my user persona, and user experience map. Overall, learning about this phenomena helped me clarify the scope of the problem, and fine tune my project goals.

The psychology behind sleep procrastination

I dove in deeper into the psychology behind the problem and found various explanations for the phenomena. For example, some research suggests that people fail to fall asleep on time, even though they are aware of their procrastination. This creates an intention-behavior gap for the individual, which stems partly from low levels of self-regulation or self-control. In fact, the problem I was formulating aligned with this explanation because it shown that “our capacity for self control is at its lowest at the end of the day”, and “daytime demands at work or school reduce the reserves of self control for the evening.”

How is my intervention addressing this?

I decided that my solution would help close this intention-behavior gap. And in order to create a robust product that could do this, I needed to learn how behavioral science addressed and explained these gaps. I found two concepts in the field that helped me formulate the concept for my product:

Commitment Devices

Additionally, behavioral scientists have been studying commitment devices as a way to close the intention-behavior gap. These are tools that attempt to change the pattern of non-compliance that comes from conflicting motivations and behaviors. For commitment devices to work, they must be voluntary, and add a cost when the person doesn’t act according to their intentions. This cost can be social, financial, or friction based.

Present bias

Behavioral science explains that we engage in hyperbolic discounting or present bias. This is an inclination to choose immediate rewards over rewards that come later in the future, even if those immediate rewards are smaller. Research showed that future focus priming, or exposing an user to a stimulus (i.e. word) to influence their response to a second stimulus (i.e. prompting a choice), was an effective way of reducing this cognitive bias.

Getting ready to ideate

This additional research informed my design decisions and allowed me to be more precise in the steps that followed. In summary, I learned:

What’s the problem (sleep procrastination)

What’s my goal (reduce the intention-behavior gap)

How to address it (future focus priming and cost-based commitment devices)

Ideation

Core Epic

Authoring stories

To guide the ideation process, I authored different user stories from the perspective of Lucy Chang using the following structure:

“As a [user type] I want to [desired action] so that [I benefit]”

I expanded Lucy’s experience map with 32 user stories that identified desired behaviors and outcomes. Then, I grouped the 32 stories under 6 distinct epics to find similarities and prioritize their relevance. Lastly, I chose 1 epic to start developing my user task flow.

I chose the epic “I want to control my sleep procrastination,” because it aligned the best with the problem space. This epic attempts to convey three aspects of the current problem formulation:

Sleep procrastination (or while-in-bed procrastination) is different from bedtime procrastination

Users don’t want to give up their late night phone use, but instead engage with it more intentionally so that they can fall asleep on time.

Controlling procrastination can be leveraged in the long term to change behavior. In this case the user can gradually adjust to an earlier fall-asleep time, and in return receive better sleep and more control over their screen time.

User Task flow

Primary task

I selected one user story from my core epic to represent the value proposition of my product in the form of an user task. Based on this story, I created a step by step flow that depicts Lucy’s interactions with the app, as she sets up a screen time plan.

Epic: I want to control my sleep procrastination

User story: “As a sleep procrastinator, I want to plan for how long I’ll use my phone in bed, so that I stay within my limits.”

Task: Create a screen time plan.

Prototype

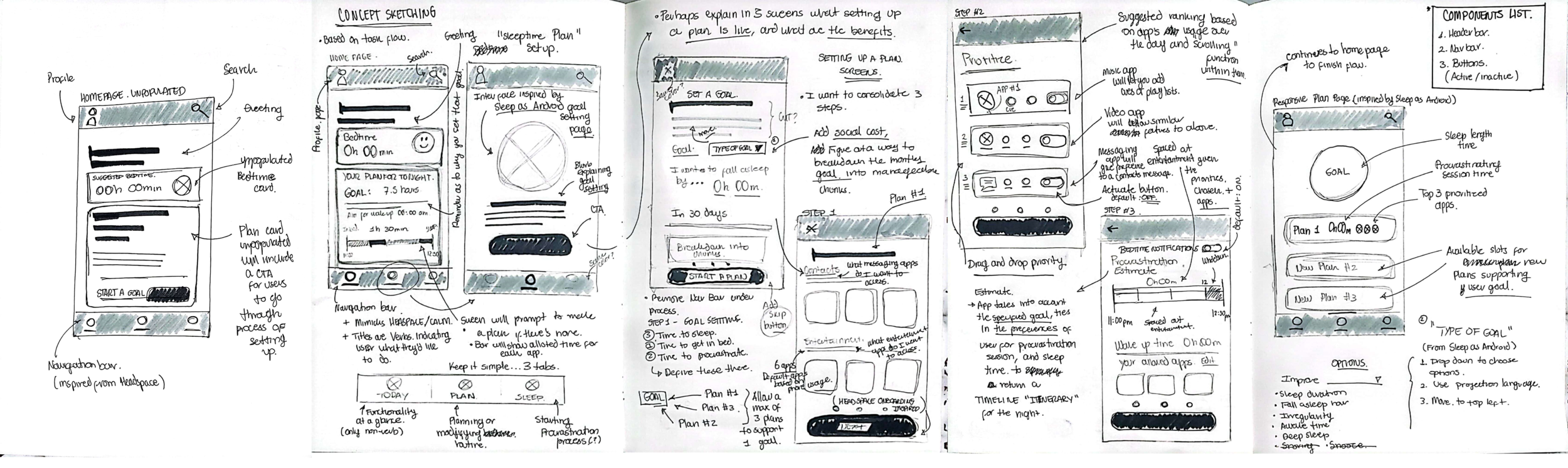

Inspiration Board and Paper Sketches

Exploration sketches

I used InVision to compile inspiration from Dribbble, Headspace, Calm, and Sleep as Android. I used this inspiration board as a guide to sketch out solutions on pen and paper of my initial concept screens. Below are the sketches that served as the starting point for my first wireframe.

From the sketches I created a list of basic components on Figma, following Material Design principles. Rapidly assembled grayscale wireframes, and created a functional prototype for user testing. The objective for this phase was to engage in a quick user-centered iteration process to challenge my assumptions before moving into UI design.

User Testing

Receiving feedback

I conducted two rounds of usability tests with 5 different participants each round. The user feedback tested my assumptions about design components, layouts, spacing, information architecture, and flow. Doing user testing improved my design and ironed out sources of friction.

The users performed 5 tasks in real time, speaking out loud, and offering their take on the concept. I recorded their interactions with different parts of the prototype, weighing them against the completion of each task and their understanding of the application.

After each round of testing, I analyzed the outputs by condensing my notes into action points on a prioritization matrix. Overall, I iterated through 3 prototypes and addressed four major issues.

Issue #1 - Goal Setting Page

Users found this screen inconsistent and difficult to understand within the overall flow of the prototype. The first iteration had underdeveloped copy and more fields to interact with, which created friction for users. In the middle version I streamlined the information on the screen, which users found easier to navigate. In the final version, I used proximity and foreground/background to distinguish between fields, and complement the text hierarchy.

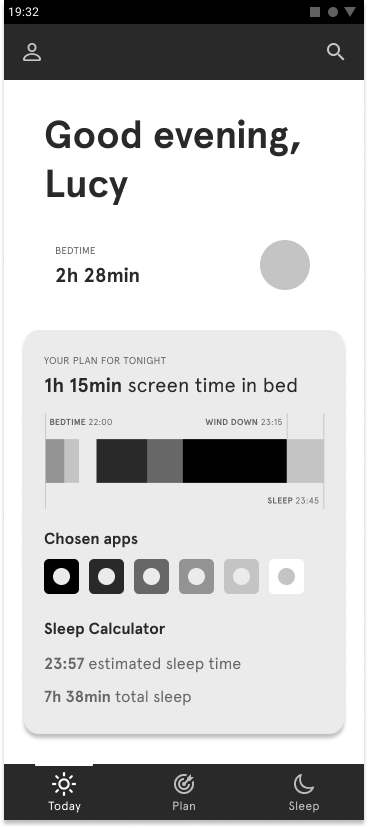

Issue #2 - Custom Screen Time Page

In earlier versions of this screen, users didn’t have a good understanding of this step. Particularly, testers didn’t know how to read the graph. After some research on app design patterns, I finally arrived at a simple horizontal bar chart to display the time. This change made all the difference, for now users were able to read and understand the information being displayed.

Issue #3 - Home Tab

In earlier iterations, the users wanted to see the information they had just inputted in a more concise manner. I decided to use cards to organize the information into digestible chunks, and type size to create a subtle visual hierarchy. Users responded positively to this change, though I’d like to continue experimenting with other layouts that can streamline the information even further.

Issue #4 - Task Flow Framing

Through user testing I found that my current task flow was missing steps. In the early prototype, users were not clear how to use the application after setting up a sleep goal and sleep target. In other words, there was no information that provided context for their interactions. Providing this context was a tough challenge, as it meant going back in my process. But consulting with other designers helped me interpret the feedback, and make the necessary changes quickly and effectively. In the new task flow I built the narrative as a first time sign-up, included walk-through screens and confirmation screens. This framed the process in a way that provided the user with context before major points of interaction.

Final prototype

After the final round of iterations I had a grayscale prototype that was backed with extensive secondary and primary research. It was time to start building a brand identity through UI and a high fidelity prototype.

Building the Brand

Visual Identity

Creating a brand

With the prototype phase over, I started developing a brand identity for the product and a high fidelity prototype.

Keywords

What identifies my brand

I brainstormed a set of keywords that identified my brand’s personality. Then, I grouped the terms into themes that embodied the brand identity. Below are each of the themes and keywords:

TRUST (Reliable, timely, effective, impactful, new)

SOFT (sleep, calming, relaxing, unwind, rest)

DARK (bedtime, early, night, evening, dusk)

RESPONSIBLE (conscious, intentional, mindful, agency, procrastination, control)

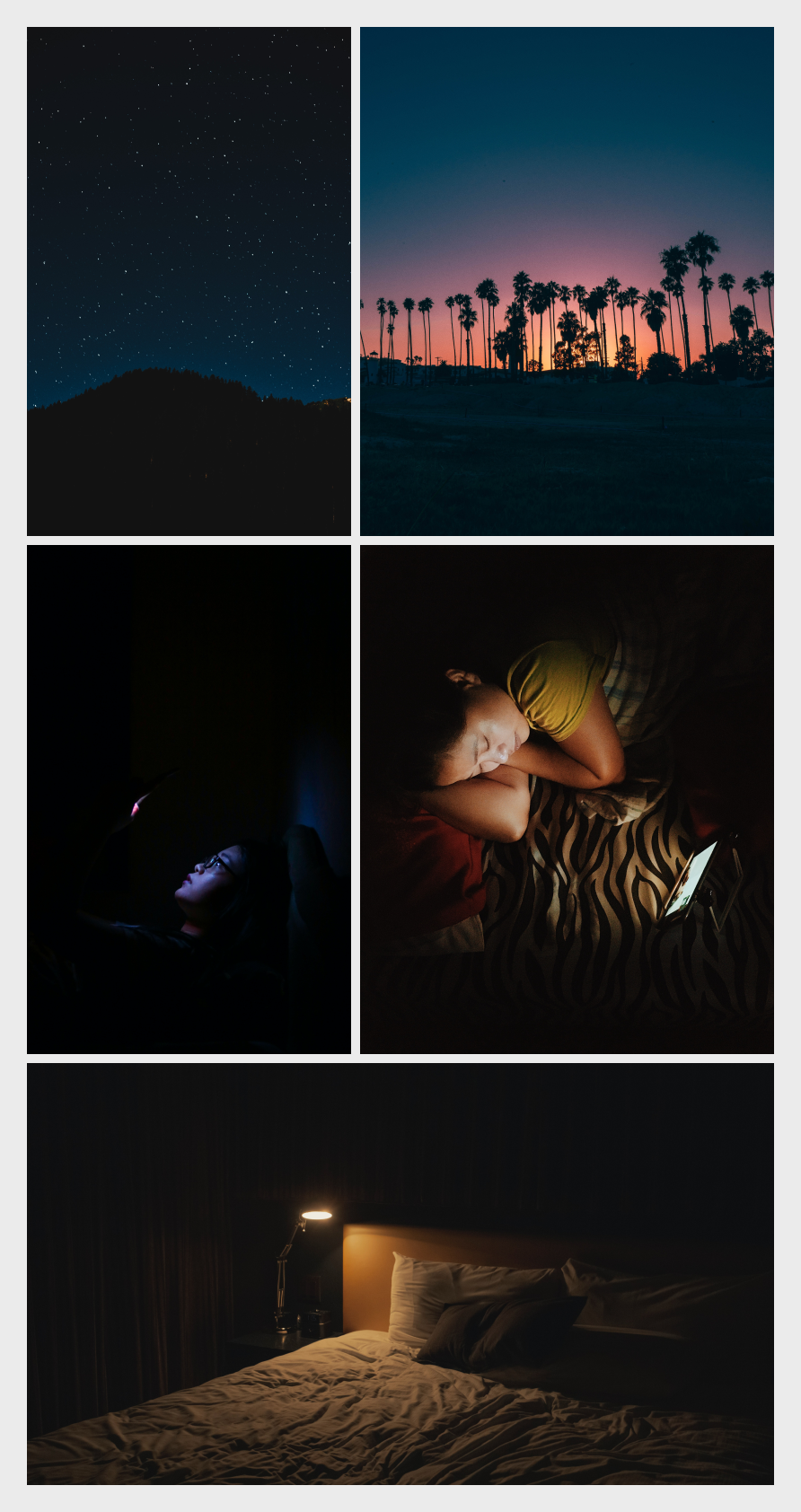

Mood Board, Color Palette, and Typography

The look and feel

Using the themes, I searched for images to curate a mood board. This became a source of inspiration and guidance for my design process. For example, I used the mood board to extract colors and curate a color palette, as well as establish my typography system.

App Name and Wordmark

What’s in a name?

Initially I was leaning towards functional names only, but as I tested different names with users, Sleeper became a favorite among them. It was short, catchy, and it offered room for creativity.

The main idea of the wordmark was to keep it simple, while maintaining a degree of nuance in the design. In the final version, I made subtle changes to the angle of lettering and injected color. Additionally, I removed the last “e” to create rhythm and embrace a modern take that would appeal to my target audience.

High Fidelity Prototype

Sleepr is born

After going through different color iterations, I finally arrived at the final high-fidelity prototype.

Value Proposition

Why it matters

Sleepr helps you manage your sleep procrastination

Sleepr lets you add up to six apps to create a custom screen time plan. The app will remind you when it’s time to put away your device and fall asleep, so that you don’t end up sleep procrastinating.

Sleepr helps you fall asleep on time

By setting up a sleep goal, Sleepr can customize a sleep plan for any day of the week, for a given sleep and wake up time. Start by setting up a range of time you’d like to fall asleep at.

Stay accountable by inviting a referee

Sleepr will also help you stay accountable by inviting a friend to follow your journey to fall asleep earlier. They will receive an email whenever you are not meeting your goal, and will be encouraged to cheer you on.

Expanding the Brand

Marketing

For the purpose of our go-to market strategy, I developed a responsive website to help communicate our value to prospective users.

The design process involved gathering UI inspiration, creating sketches, and doing multiple rounds of design iterations in grayscale wireframes. Ultimately this process took me from a low fidelity design to a high fidelity prototype. I employed a similar strategy as with the design of the mobile app, such as doing rounds of user testing to find friction points.

The website serves three purposes:

Educate prospective users on what Sleepr is and how it’s differentiated.

Elicit conversion in prospective users by building trust and communicating our value

Act as a funnel within a larger integrated marketing strategy to acquire users

Monetization

To develop the monetization strategy for the application I need to explore different financial models for similar products. Also, solidify things like development costs, funding, and app maintenance. For now, a subscription based model and one time payment model seem attractive. Though, financial projections will help explore the most viable.

Promotion

In the early stages of our go-to-market strategy the referee feature will help other users find our application. I seek to leverage network effects through the referee invitation, and build momentum through practical word of mouth. In essence, a referee invitation is a way for users to establish a commitment device, and for our brand to receive more exposure within their circle.

Coming Next

Next Steps

Explore other user stories and create a new task flow that touches on the “sleep” capabilities of the application. Specifically, I’d like to answer questions such as “what happens when the user’s screen time plan runs out?” or “what does a successful/unsuccessful engagement with a screen time plan look like?”

Consult with a software developer to explore the next steps that go into building an MVP for a market test.

Draft a business plan to prepare for fundraising. Emphasizing the marketing strategy and financials.

Key Takeaways

Don’t be scared to look back

During this project I learned the value of revising my previous work. For example, as I conducted user interviews, I learned that my task flow needed revision to better contextualize the user story. Going back was difficult, especially because of the time constraints, but ultimately redesigning that task flow allowed me to put together a prototype that users found easier to interact with.

Think & design strategically

Though going back and making changes is important, it’s important to select those changes well. During this project I learned that designers need to think strategically and consider potential “domino effects” that might come from a revision. For example, what I thought were minor cosmetic enhancements, would sometimes cascade into a major set of changes.

Rely on colleagues

My colleagues were essential in challenging my thinking and helping me set priorities. Working with multiple projects requires that we stay on track at all times to meet the needs of the overall team. In this case, even as an individual project, I found that I needed to run my action plan through others before engaging in it. This resulted in a fresh set of eyes asking questions that I had missed, or simply serving as a source of encouragement.

Sources

https://www.cedars-sinai.org/health-library/diseases-and-conditions/s/sleep-deprivation.html

Zitting, K. M., Münch, M. Y., Cain, S. W., Wang, W., Wong, A., Ronda, J. M., Aeschbach, D., Czeisler, C. A., & Duffy, J. F. (2018). Young adults are more vulnerable to chronic sleep deficiency and recurrent circadian disruption than older adults. Scientific reports, 8(1), 11052. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29358-x

https://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/technology-sleep.html

https://www.today.duke.edu/2017/02/people-far-urban-lights-bright-screens-still-skimp-sleep

Bruce, E. S., Lunt, L., & McDonagh, J. E. (2017). Sleep in adolescents and young adults. Clinical medicine (London, England), 17(5), 424–428. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.17-5-424

https://www.healthline.com/health/dr/sleep-deprivation/sleep-debt

https://www.cedars-sinai.org/health-library/diseases-and-conditions/s/sleep-deprivation.html

https://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/technology-sleep.html

https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-hygiene/revenge-bedtime-procrastination

https://medium.com/behavior-design-hub/your-commitment-devices-database-35a54df3a64f